Lorca is now a national trademark, a potent icon whose valuable wares are exported across the global cultural marketplace. More so than any other twentieth-century Spanish writer, he remains a paradoxical embodiment of the local, the national and the global. His life and work have become indelibly bound up in a process of mythification that has converted him first into the ultimate countercultural icon—the gay, martyred seer and a taboo topic in Franco’s Spain—and now the establishment face of the newly tolerant post-dictatorship Spain. (2)Delgado’s reading of Lorca’s iconographic role in Western culture not only suggests why it is important to know about Lorca’s biography and who he is, but it also speaks to many of the questions at the heart of our play about the performative nature of identity and how this everyday experience is enacted and reified in the theatre, suggesting that Lorca’s interest in a dual identity was connected to his own personal experiences. In order to fully understand Lorca’s relationship to performance, myth and the dual identity, we must look to his life.

Timeline:

1898: Federico García Lorca is born 5 June in his Father’s hometown of Fuente Vaqueros, a small farming village in the province of Granada (Cuitiño 4). His father, Federico Lorca Rodrígez, was a wealthy landowner whose second wife, Vicenta Lorca Romero, was Lorca’s mother and a school teacher. Lorca was one of three siblings, Francisco (Paco), Concha and Isabel, and was very much brought up as “a rich little boy in the village,” which he later resented (Cuitiño 5, Stainton 15). As a child, Lorca was surrounded by influential role models of talent, creativity and intelligence, especially by relatives who were excellent musicians and singers. One of the most important was his great-uncle Baldomero García Rodriquez who sang in the cante jondo, or deep song, style of the Andalusian gypsies, about which Lorca would later theorize (Cuitiño 6).

Lorca with his family, c. 1912

He also showed an early fascination with drama and Catholic liturgy, delivering long sermons in imitation of the priest at mass or setting up elaborate pageants, and one of his first toys was a miniature puppet theatre (Cuitiño 8, Stainon 13). 1898 is also the same year that Spain lost the last of its overseas possessions, including Cuba, in the Spanish-American War, suggesting that this revolutionary poet was born in a year of great changes (Cuitiño 4). This year is also used to refer to a group of influential Spanish authors, including Basque Unamuno and Ramón del Valle-Inclán, known as the Generation of ’98 who sought to “restore Spain’s eminence…with the indomitable Spanish spirit” (Cobb 17). Lorca’s own Generation of ’27 is greatly influenced by this earlier group of writers.

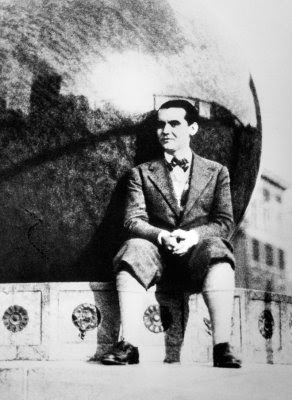

Lorca, age six.

1909: Lorca moves to a house called Huerta de San Vicente in Granada with his family where he attends the private Sacred Heart of Jesus Academy and the General and Technical Institute as well. Lorca, however, was never a good student and for the rest of his student career, Lorca was constantly battling his parents who insisted he pass his exams and his stodgy professors who saw him as “a wayward dreamer” (Stainton 28). Despite his difficulties at school, Lorca “read avidly” and studied music, “his greatest love,” with Antonio Segura Mesa (Stainton 23, 26).

The Huerta de San Vicente, named after Lorca's mother.

Lorca's family outside the Huerta.

Reading to his youngest sister Isabel, 1914.

1915: Lorca attends the University of Granada where he studies philosophy, literature and law, despite his lack of interest in school. Soon, he begins “his first nocturnal scirbblings” of poetry and plays while studying the piano and attending lectures during the day (Cuitiño 11). He also joins El Rinconcillo, or “The Little Corner,” a group of students and artists that met at the back of the Alameda Café. While Lorca began to write and to collaborate with this tertulia, or literary group, he mostly spent his time on the café’s little piano. Nevertheless, Lorca fervently took up the Rinconcillo’s mission to “reform and revitalize Granada” and its culture that they saw as threatened by modernization, a passionate for his home that would bleed through all of Lorca’s work (Stainton 33, Gibson 4).

1918: Impressions and Landscapes is published based upon Lorca’s travels through Spain several years earlier with his beloved professor Martín Domínguez Berrueta. This book, however, was dedicated to Lorca’s music teacher, Antonio Segura Mesa. About this time Lorca also meets the composer Manuel de Falla, an important figure in his early career (Cuitiño 12). Although this year marks the end of the First World War, Lorca becomes eligible at age 20 for the draft and his parents pay a doctor to proclaim him “unfit” for the military, possibly changing the fate of his career (Stainton 55).

1920: Lorca moves into the Residencia des Estudiantes in Madrid after his father refuses to allow him to study music in Paris. Like his “pampered existence” at home in Granada, Lorca lives very comfortably at this elite, liberal-minded residence hall modeled after Oxbridge and designed for Spain’s brightest new thinkers (Stainton 62). Lorca flourished among the Resi students, “his daily life…a performance” with music and poetry recitals and attendance at the tertulias, or literary gatherings, at local cafés, where Lorca is exposed to modernismo, the avant-garde, cubism, futurism and Dada (Stainton 63). His first play, The Butterflies Evil Spell is produced. It was a huge flop (Cuitiño 16).

1921: Book of Poems, began in 1917, is published. Lorca also begins writing Poem of the Deep Song, already thinking about the cultural importance of the cante jondo music that embodies Lorca’s poetics.

1922: Lorca and Manuel de Falla organize a cante jondo festival in Granada to promote this traditional, popular, folk music associated with the gypsies and the Moors of Granada before flamenco became the dominant style (Maurer). This same year Salvador Dalí arrives at the Resi and Lorca works on his Billy Club Puppet plays, including The Tragicomedy of Don Cristobál and Miss Rosita.

First edition cover for Poem of the Deep Song

1923-25: Lorca graduates (somehow) with a degree in law in 1923 and spends his time writing and goofing off with Dalí and Luis Buñuel in Madrid. In 1925, he visits Dalí’s family Cadaqués where he falls in love with Dalí’s family, the seaside and with Dalí himself. Lorca begins to work on Gypsy Ballads, Songs, and Mariana Pineda, of which he gives a memorable reading to Dalí’s family, during these years. During the summer of 1925 he returns home to Granada and spends a restless and melancholy time away from his friend, composing several short pieces including “Buster Keaton’s Stroll,” his “Ode to Salvador Dalí,” and “Dialogue with Luis Buñuel” (Stainton 126-136).

1926: Writes his essay, “The Poetic Image in Don Luis de Góngora,” the Golden Age symbolist poet so admired by his contemporaries, and the first version of The Shoemaker’s Prodigious Wife (Delgado 19). His “Ode to Salvador Dalí” is published (Cobb 15). He also meets the popular actress Margarita Xirgu, who helps him to produce Mariana Pineda in Barcelona at the Teatro Goya (Cuitiño 39).

1935: Lorca writes Doña Rosita the Spinster, or the Language of Flowers, also starring Xirgu, and the play is performed in Barcelona in December (Cuitiño 114). Lorca also meets Dalí one more time in Barcelona, abandoning a poetry and music recital in his honor to spend a few hours with his estranged friend in stead. Lorca later described this meeting as proof that they were “twin spirits” because after “seven years without seeing each other” they “still [agreed] on everything as if [they’d] never stopped talking” (Maurer 26).

Cobb, Carl W. Federico García Lorca. New York, NY: Twayne Publishers. 1967. Print.

Cuitiño, Luis Martínez. García Lorca For Beginners. New York, NY: Writes and Readers Publishers, Inc. 2000. Print.

Delgado, Maria M. Federico García Lorca. New York, NY: Routledge. 2008. Print.

Gibson, Ian. The Death of Lorca An Investigation Establishing the Guilt for One of the Great Crimes of the Spanish Civil War. Chicago, IL: J. Philip O’Hara, Inc. 1973. Print.

Stainton, Leslie. Lorca: A Dream of Life. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 1999. Print.

1923-25: Lorca graduates (somehow) with a degree in law in 1923 and spends his time writing and goofing off with Dalí and Luis Buñuel in Madrid. In 1925, he visits Dalí’s family Cadaqués where he falls in love with Dalí’s family, the seaside and with Dalí himself. Lorca begins to work on Gypsy Ballads, Songs, and Mariana Pineda, of which he gives a memorable reading to Dalí’s family, during these years. During the summer of 1925 he returns home to Granada and spends a restless and melancholy time away from his friend, composing several short pieces including “Buster Keaton’s Stroll,” his “Ode to Salvador Dalí,” and “Dialogue with Luis Buñuel” (Stainton 126-136).

1926: Writes his essay, “The Poetic Image in Don Luis de Góngora,” the Golden Age symbolist poet so admired by his contemporaries, and the first version of The Shoemaker’s Prodigious Wife (Delgado 19). His “Ode to Salvador Dalí” is published (Cobb 15). He also meets the popular actress Margarita Xirgu, who helps him to produce Mariana Pineda in Barcelona at the Teatro Goya (Cuitiño 39).

1927: Lorca’s drawings are exhibited in Barcelona in June and Lorca again stays with Dalí and his family in Cadaqués. Mariana Pineda premiers in Madrid. Later that year Lorca travels to Seville with a group of writers representing the “new Spanish literature” for a three-day celebration of the tricentennial of Góngora’s death, and this group of writers became known as the Generation of ’27 (Stainton 173).

In Cadaqués while staying with Dalí and Ana María, his sister, in 1927

1928: Lorca releases his avant-garde magazine gallo, featuring Buster Keaton’s Stroll (written in 1925) in the second issue. In April, he published Gypsy Ballads, which Dalí harshly criticizes for its return to the traditional. By this time, Lorca and Dalí have fallen out. However, Lorca begins an affair with the young, exotic-looking artist, Emilio Aladrén (Stainton 181). Lorca delivers one of his only other lectures, “On Lullabies.” He also writes Don Perlimplín and Don Christóbal.

1929: In June, Lorca goes to New York City with one of his closest friends, Fernando de los Ríos, where he begins working on Once Five Years Pass and The Public, composes the first version of Yerma and writes the poems that will become perhaps his most famous collection, Poet in New York. Overwhelmed, speaking almost no English and homesick, Lorca enrolled at Columbia University and took a student dorm room. Lorca quickly made friends, but never really learned English, using bizarrely elaborate gestures, a small dictionary, and conversational French to get around and spending time with other Spanish-speakers. Though at first Lorca was in awe of “Dalí’s machine-age aesthetic come to life,” he would soon see the “rootlessness” city as “an alien metropolis where life has no value,” to which he would constantly compare his lost childhood in rural Spain (237). He witnessed death, poverty, cruelty and the Stock Market Crash. Even the greater freedom around homosexuality and his interest in Harlem jazz culture only reminded him of the isolation he felt because of his sexuality, expressed in many of his poems, and the discrimination faced by Blacks in America that reminded him of the persecuted Moors and gypsies in Granada. When he took a short trip to visit a friend in New English, Lorca declared “Ay! I’ve left the dungeon!” (226).

1928: Lorca releases his avant-garde magazine gallo, featuring Buster Keaton’s Stroll (written in 1925) in the second issue. In April, he published Gypsy Ballads, which Dalí harshly criticizes for its return to the traditional. By this time, Lorca and Dalí have fallen out. However, Lorca begins an affair with the young, exotic-looking artist, Emilio Aladrén (Stainton 181). Lorca delivers one of his only other lectures, “On Lullabies.” He also writes Don Perlimplín and Don Christóbal.

1929: In June, Lorca goes to New York City with one of his closest friends, Fernando de los Ríos, where he begins working on Once Five Years Pass and The Public, composes the first version of Yerma and writes the poems that will become perhaps his most famous collection, Poet in New York. Overwhelmed, speaking almost no English and homesick, Lorca enrolled at Columbia University and took a student dorm room. Lorca quickly made friends, but never really learned English, using bizarrely elaborate gestures, a small dictionary, and conversational French to get around and spending time with other Spanish-speakers. Though at first Lorca was in awe of “Dalí’s machine-age aesthetic come to life,” he would soon see the “rootlessness” city as “an alien metropolis where life has no value,” to which he would constantly compare his lost childhood in rural Spain (237). He witnessed death, poverty, cruelty and the Stock Market Crash. Even the greater freedom around homosexuality and his interest in Harlem jazz culture only reminded him of the isolation he felt because of his sexuality, expressed in many of his poems, and the discrimination faced by Blacks in America that reminded him of the persecuted Moors and gypsies in Granada. When he took a short trip to visit a friend in New English, Lorca declared “Ay! I’ve left the dungeon!” (226).

In New York outside Columbia University, 1929

Self Portrait in New York, 1929

First edition of Poet in New York, first bilingual edition published in 1940.

However, Lorca also thought that American theatre was “revolutionary” and wrote to his family that, “Everything that now exists in Spain is dead. Either the theatre changes radically or it dies away forever” (232). In 1930, Lorca joyously goes to Cuba before returning to Spain, describing his time in New York as “the mot useful experience of my life” (241). He embraced Havana with energy and warmth, “donned a white linen suit, turned his face towards the light, and settled into the relaxed rythms of island existence” (244, Stainton 214-244).

Lorca in Havana, Cuba on his way home to Spain.

With his brother Francisco, 1930.

1931: Back in Spain, Lorca becomes the artistic director of La Barraca, a state-run traveling theatre troupe founded by students and faculty of the University of Madrid. As a part of the “Missiones Pedagógicas” program of the new Republic, the “socially engaged” theatre focused on making plays from the Golden Age canon accessible and relevant to a rural audience through simple staging, music, and new settings. This marked the start of battles with right-wing critics and the Catholic Church who abhorred Lorca’s socialist, “homosexual” company. As part of this popular movement for education and social consciousness, Lorca opens a library in his hometown Fuente Vaqueros (Delgado 28-31). Poet in New York is published.

1931: Back in Spain, Lorca becomes the artistic director of La Barraca, a state-run traveling theatre troupe founded by students and faculty of the University of Madrid. As a part of the “Missiones Pedagógicas” program of the new Republic, the “socially engaged” theatre focused on making plays from the Golden Age canon accessible and relevant to a rural audience through simple staging, music, and new settings. This marked the start of battles with right-wing critics and the Catholic Church who abhorred Lorca’s socialist, “homosexual” company. As part of this popular movement for education and social consciousness, Lorca opens a library in his hometown Fuente Vaqueros (Delgado 28-31). Poet in New York is published.

Traveling with La Barraca.

With his co-director of La Barraca in their company uniforms.

With neice Tica, 1931

1933: Under the new conservative catholic majority in government, La Barraca is no longer subsidized by the state. Blood Wedding premiers in Madrid on 8 March, a play that revisits many of the themes and symbols from Gypsy Ballads and reflects Lorca’s view of “rural Spanish life…as innately tragic” (Cuitiño 82, Stainton 298). Lorca also travels to Argentina in October for productions of Blood Wedding, Mariana Pineda, and The Shoemaker’s Prodigious Wife. It is here in Latin America where Lorca first achieves real commercial success as a theatre artist and becomes known as a “pan-Hispanic” writer (Dalgado 18). In Buenos Aires, Lorca delivers his essay “Play the Theory of the Duende” to an enthusiastic audience (Maurer viii).

1934: He writes his "Lament for the Death of Ignacio Sánchez Mejías," a famous bullfighter and friend of Lorca’s whom he and the Generation ’27 greatly admired. Yerma premiers in Madrid at the end of the year, drawing great support from the “left liberal intelligentia” because its director and lead actress were associated with the Republicans and Lorca himself was increasingly seen as a leftist figure (Delgado 32, Cuitiño 107).

1933: Under the new conservative catholic majority in government, La Barraca is no longer subsidized by the state. Blood Wedding premiers in Madrid on 8 March, a play that revisits many of the themes and symbols from Gypsy Ballads and reflects Lorca’s view of “rural Spanish life…as innately tragic” (Cuitiño 82, Stainton 298). Lorca also travels to Argentina in October for productions of Blood Wedding, Mariana Pineda, and The Shoemaker’s Prodigious Wife. It is here in Latin America where Lorca first achieves real commercial success as a theatre artist and becomes known as a “pan-Hispanic” writer (Dalgado 18). In Buenos Aires, Lorca delivers his essay “Play the Theory of the Duende” to an enthusiastic audience (Maurer viii).

1934: He writes his "Lament for the Death of Ignacio Sánchez Mejías," a famous bullfighter and friend of Lorca’s whom he and the Generation ’27 greatly admired. Yerma premiers in Madrid at the end of the year, drawing great support from the “left liberal intelligentia” because its director and lead actress were associated with the Republicans and Lorca himself was increasingly seen as a leftist figure (Delgado 32, Cuitiño 107).

One of Lorca's Sailor drawings

Montevideo, 1934.

1935: Lorca writes Doña Rosita the Spinster, or the Language of Flowers, also starring Xirgu, and the play is performed in Barcelona in December (Cuitiño 114). Lorca also meets Dalí one more time in Barcelona, abandoning a poetry and music recital in his honor to spend a few hours with his estranged friend in stead. Lorca later described this meeting as proof that they were “twin spirits” because after “seven years without seeing each other” they “still [agreed] on everything as if [they’d] never stopped talking” (Maurer 26).

Reading his latest script for Doña Rosita in Barcelona, 1935.

With Margarita Xirgu in Barcelona, 1935

At home in Granada at the piano, 1935.

1936: First Songs, written in 1922, is published. In July, Lorca returns home to Granada to escape the dangers of Madrid with outbreak of the Spanish Civil War. On 16 August Lorca is arrested by the Civil Government under the Nationalist Movement at the home of his friend, Luis Rosales. On the morning of 19 August he is executed outside the city (Gibson).

Works Cited:

1936: First Songs, written in 1922, is published. In July, Lorca returns home to Granada to escape the dangers of Madrid with outbreak of the Spanish Civil War. On 16 August Lorca is arrested by the Civil Government under the Nationalist Movement at the home of his friend, Luis Rosales. On the morning of 19 August he is executed outside the city (Gibson).

Works Cited:

Cobb, Carl W. Federico García Lorca. New York, NY: Twayne Publishers. 1967. Print.

Cuitiño, Luis Martínez. García Lorca For Beginners. New York, NY: Writes and Readers Publishers, Inc. 2000. Print.

Delgado, Maria M. Federico García Lorca. New York, NY: Routledge. 2008. Print.

Gibson, Ian. The Death of Lorca An Investigation Establishing the Guilt for One of the Great Crimes of the Spanish Civil War. Chicago, IL: J. Philip O’Hara, Inc. 1973. Print.

Maurer, Christopher. "Introduction." In Search of Duende. Federico García Lorca. New Directions. 2010. Print.

Sawyer-Lauçanno, Christopher. “Introduction.” Barbarous nights: legends and plays from the Little theater/Federico Garcia Lorca, Trans. Christopher Sawyer-Laucanno. San Francisco, CA: City Lights Books. 1991. Print.

Stainton, Leslie. Lorca: A Dream of Life. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 1999. Print.

No comments:

Post a Comment