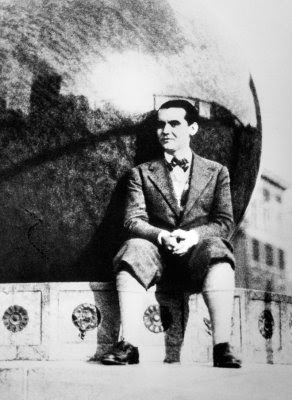

Lorca and Dalí in Cadaqués, 1927

The “legendary friendship” of Lorca and Salvador Dalì began in 1923 when Dalí arrived at the Residencia de Estudiantes in Madrid to study at the Special School of Drawing at the Academy of San Fernando (Maurer 3). The first time they met, Lorca was amazed by Dalí’s unconventional style of dress while Dalí “in turn, was captivated by Lorca” and his first impression of Lorca was of a “poetic phenomenon in its entirety and ‘in the raw’ appearing suddenly before me in flesh and blood” (Stainton 110-1). Despite their antithetical personalities (Dalí was very shy while Lorca was “a font of laughter and music”) and frequent disagreements about art and literature, Dalí and Lorca became fast friends and Lorca helped Dalí integrate into social life at the Resi (Stainton 111). Though Dalí was expelled for participating in a student protest, only to participate in yet another political demonstration at home where he spent a month in prison, the artist was back at the Resi in 1924 with a new “maniacal zeal” for the avant-garde that became infectious (Stainton 127).

Lorca and Dalí at a fair in Barcelona, mid-1920s

Luis Buñuel, c. 1920

Along with Luis Buñuel, the filmmaker studying science at the time, and other friends, they spent their time at the Resi together talking, drinking, smoking, reading to each other, and playing countless practical jokes and games. Lorca and Buñuel dressed up like nuns and harassed people on the trolly and they all joined Buñuel’s made-up fraternity of Toledo, which involved a trip to the city for a night of drunken antics. Lorca and Dalí made plans for a “book of putrefactions,” or anything they thought was “outmoded, sacred or anachronistic,” or as Dalí defined the term, “EMOTION” (Stainton 128-9). The “near-constant companions” developed a friendship of “mutual awe, but also, increasingly, of love” (Stainton 129).

Lorca, Portrait of Dalí, c. 1925.

Between 1925 and 1927 the relationship between Dalí and Lorca grew as their admiration for one another and their influence over each other’s work intensified. Lorca fell in love with Cadaqués, a coastal village just north of Barcelona, where he went to stay over Easter holiday in 1925 with Dalí and his family in their summer home there. There, they spent their time walking through town, laughing with Ana María, Dalí’s beautiful sister, wandering the beach and watching each other work (Stainton 130-132). Lorca became the family’s “second son” after reading his play Mariana Pineda, which Dalí for which would later design the set for its premier in Barcelona (Stainton 132). He traveled with the family back to their home in the town Figueres for a reading of his play and poetry, but soon went home to Granada and spent the next year moving between Granada and Madrid desperately missing his friend and keeping steady correspondence with Dalí as their work grew ever closer. While the two spent time together again in the summer of 1927 for the premier of Mariana Pineda in Barcelona and then went to Cadaqués, something happened that led Lorca to suddenly return to Granada. Dalí was soon drafted into the Spanish army for a year, separating the friends even further. Lorca returned to Madrid again to work and participate in the Luis de Gongóra festival then went home once again to Granada where he realized that his relationship with Dalí had irreversibly changed (Stainton 132-178). By 1928, they were both personally and artistically estranged from each other, moving in two different directions, only to meet briefly once more in 1935 (Maurer 4).

,+1925.jpg)

From a letter to Dalí, 1925

Dalí with his sister, Ana María Dalí in Cadaqués, 1927.

Lorca with Dalí in uniform, 1927

Despite each man having his own distinctive approach to art and poetry and the ways in which they eventually became increasingly critical of each other’s work, Lorca and Dalí both had considerable influence over how their work evolved between 1923 and 1928. Early on in their relationship at the Resi Dalí and Lorca were exposed together to the latest in art, literature and music, including American jazz and Buster Keaton films, and they fueled each other’s interest in modernism and the avant-garde developing in Europe (Stainton 128). Soon, they were showing up frequently in each other’s work. Lorca’s famous “Ode to Salvador Dalí,” written during his first long separation from Dalí in 1925, captured both Lorca’s deep feelings for the artist as well as his “cubist ideals” and “dispassionate, analytical approach to reality” captured in the poem’s “rigid, ordered, classical” style (Stainton 141). In Dalí’s paintings from the period it is not uncommon to spy Lorca’s head floating amidst torsos, severed limbs and “rotting animals,” as in his famous works “Little Ashes” and “Honey is Sweeter than Blood,” and he began to paint Lorca’s face overlapping with his (Stainton 165, 166).

Honey is Sweeter than Blood.

While Dalí began to write more, Lorca began to draw more and Dalí helped him to exhibit his paintings in Barcelona at the Dalmau Gallery in June 1927. Not only do his drawings from this show reflect the extent to which “[Lorca] had absorbed [Dalí’s] cubist aesthetic and…enthusiasm for surrealism,” but they also reveal the deep understanding of one another that these artists shared (Stainton 163). They developed their own “private vocabulary” of motifs and images in their letters to each other, such the meaning surrounding the figure of St. Sebastian, and experimented together with the same “surrealist techniques,” like “automatic writing and drawing” and with “dream images” (Stainton 168). Dalí was also a great source of encouragement to Lorca as he published his first poetry collections and praised his emerging plays and books (Stainton 151, 155).

Dalí, Little Ashes, 1928. Lorca's image can be seen towards the bottom just right of center.

However, by 1928, the two friends had a falling out reflected in their personal histories and in their divergent aesthetics. For Dalí, art became about objectivity, strange juxtapositions, “anti-art,” “the surface of things,” and must “let go of the anti-rot that is historical” while Lorca remained interested in discovering “inner life,” studying the “mystery” of art and recalling a pre-Castilian past rooted in his Andalusian homeland despite his admiration for the avant-garde and surrealism (Maurer 11, 87, 8). Lorca demonstrates this dichotomy between “surface and depths, clarity and mystery” that evolved between their artistic ideas in his prose poem written in 1927 called “St. Lucy and St. Lazarus,” each symbolizing a side of the debate (Maurer 10). At this time Dalí became increasingly critical of Lorca’s work, particularly his “Andalusian altarpiece,” Gypsy Ballads. In September 1928, Dalí sent Lorca a seven-page critique of his somewhat controversial collection of “tragic tale’s of life and death,” “sensual language and baroque delight to the human body” that he described as “stereotypical and conformist” as well as “fully within the traditional” (Stainton 192, Maurer 13). However, despite his negative reaction, Dalí also wrote to Lorca, “I love you for what your book reveals you to be” and his belief that Lorca would go on to “produce witty, horrifying…intense, poetic things such as no other poet could” (Stainton 192-3).

While there is little information about what caused this separation between Lorca and Dalí, it is clear that this rift had to do with their fear and discomfort around the homosexual feelings for one another they both struggled with. Lorca, who identified his homosexual love for the artist as early as summer 1925, suffered greatly due to his awareness of the attitude of Catholic society towards homosexuality which labeled his desires “perverse” as well as his own personal fear of sex (Stainton 138). Dalí too was “obsessed by Lorca, and troubled by his obsession” (Stainton 166). The letters between Lorca and Dalí written during this period reflect this intense passion as well as unease about their love for one another.

The mystery surrounding their homoerotically charged relationship is best illustrated by their discussion of the iconic St. Sebastian who came to symbolize the growing divide in their aesthetic views as well as a potentially homoerotic relationship and who appeared throughout their letters, drawings, and paintings. Though Dalí revered the passivity and serenity in St. Sebastian’s expression while Lorca was more interested in the saint’s depiction of vulnerability and martyrdom in relation to artistic creation, both artists “were keenly aware of the intensely erotic meaning of their saint, and of a ‘penetration’ both figurative and physical” (Maurer 20). Though Dalí makes reference to both himself and Lorca as a St. Sebastian throughout his letters, in one letter in particular he remarks, “Didn’t you ever think how strange it is that his ass doesn’t have a single wound?” before finishing with his usual, “I love you very much” (Maurer 62). Is this a slightly cruel, teasingly homoerotic reference to Lorca’s desire for his friend? Is there a more personal meaning to St. Sebastian’s martyrdom for these two artists? Dalí would in fact eventually claim that Lorca was openly homosexual and that he had ultimately “spurned Lorca’s sexual advances” (Stainton 165). Some also implicate Luis Buñuel in their estrangement, suggesting that he “was appalled by the intensity of Dalí’s attachment to Lorca” and had to do with Dalí disinterest in Lorca and decision to pursue his career and the Surrealist movement in Paris (Maurer 16). Whatever happened to distance these two dear friends, it is clear that both Dalí and Lorca were indeed “wounded” by each other’s friendship and love, each irreversibly marked by the life and work of the other in a way that was befittingly tragic and poetic.

Robert Pattinson as Dalí and Javier Beltrán as Lorca in the film dramatizing their relaitonship, Little Ashes (2008).

Works Cited:

Maurer, Christopher. Sebastian’s Arrows: Letters and Mementos of Salvador Dalì and Federico Garcìa Lorca. Swan Isle Press. 2005. Print.

Stainton, Leslie. Lorca: A Dream of Life. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 1999. Print.

,+1925.jpg)